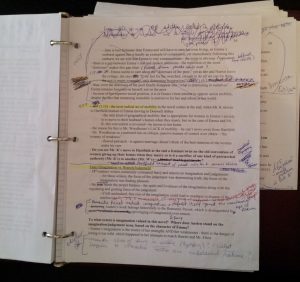

I recently taught Austen’s Emma for what felt like the millionth time. I know I need to take a break from teaching a text when my jokes feel scripted and my lecture notes are so covered with layers of hastily-scrawled notes that I can hardly read them. There are always Austen fans among the English majors in my classes, but there are even more students who find Austen’s novels boring (and who think her name and the city in Texas are spelled the same way). While Austen delighted in the small scope of her novels—“3 or 4 families in a country village”—students in our modern, relentlessly global society are often baffled by Austen’s closed, even claustrophobic world with its elaborate social rituals and subtle class distinctions.

My male students are typically uninterested in Austen’s writing, but this time I noticed a buzz of discussion from a few in the back row who usually hide behind their suspiciously-fascinating laptops. Before I could rejoice too much, I found out that the interest came from Mr. Knightley’s line about being in love with Emma since she was “thirteen at least” (he is sixteen years her senior). I did my usual shtick—yes, this line makes many modern readers raise their eyebrows, but Mr. Knightley is not a pedophile. There is no evidence that his feelings for Emma when she was thirteen are sexual, but trying to get a young person in our oversexed North American society to believe this is not easy. I kept trying to steer the conversation away from pedophilia but the student persisted to the point of becoming angry that I wanted to talk about the novel instead of the “issue.” I have no doubt that both of us left the classroom that day feeling defeated and annoyed.

Aside from the “text vs. issue” conflict, students also repeatedly demand, either implicitly or explicitly, “How is this text (or class) relevant to my life?” I hate this question because I want to say, “Not everything is relevant to your life. Why don’t you try becoming interested in something outside yourself just for the sake of learning something new?”

On the other hand, I understand the impulse behind this demand. We all want to relate to what we’re reading. It’s natural to want to know why a text is important or what we can learn from it that makes a difference to our lives. Great literature can—and should—change us.

Later the same week in which my student and I butted heads, I was thinking about family relationships and loyalty. I’m fortunate to be a stepmom who is also a stepchild. I say “fortunate” because when I don’t understand my stepmom’s behaviour, I gain insight from my own impulses as a stepmom. When I don’t understand my stepchildren’s behaviour, I gain insight from my role as stepchild.

Many years ago I overheard my dad and stepmom talking about me. He was complaining about something I’d done and she was comforting him. I was angry, believing that she had no right to take his side because she didn’t know the history between my dad and I or what motivated me to act as I did.

These days, if my husband is upset by something his kids do or say, I feel exactly as my stepmom did. I’m loyal to him, not to them. I like them but I didn’t raise them and I don’t have the automatic loyalty of a biological mom. Sometimes they are like friends whom I have interesting conversations with. Sometimes they are like a nephew or niece. But when they hurt my husband they are the enemy.

This is where my dual roles are useful. I know that it’s not my place to interfere in the fraught, love-hate relationship between parent and child. I know that my stepkids have a history with their dad that I’ll never share or understand from their point of view. I know that I hear only one side of the story.

Readers of Austen’s Emma also hear just one side of the story: the narrator’s. And the narrator’s voice is remarkably similar to Mr. Knightley’s. The narrator treats imaginative Emma with gentle irony throughout the novel, but reasonable Mr. Knightley is rarely treated this way: he is good and wise and (almost) always right. The traditional interpretation of this contrast is that Mr. Knightley ultimately corrects the excesses of Emma’s wild imagination so that by the end of the novel she becomes a proper lady.

During the proposal scene, Mr. Knightley tells Emma, “you hear nothing but truth from me,” and readers are likely to believe him. But to me the most important, yet easily-missed, line in the novel comes from the narrator after the proposal scene:

Seldom, very seldom, does complete truth belong to any human disclosure; seldom can it happen that something is not a little disguised, or a little mistaken.

Here, the narrator separates from both Mr. Knightley and Emma and states a truth they both need to learn.

I tend to believe that what my loved ones tell me is entirely true, despite the wisdom of Austen’s narrator. Case in point: my husband told me about a strange telephone conversation he’d had with an acquaintance. The way he told it, the other person was behaving illogically. His story sounded plausible, so I believed him. Then he told me that he’d been testing a cell phone recording app that day and had recorded this conversation. Out of curiosity, I listened to the interchange on his phone, but I was shocked by what I heard. It wasn’t the other person who was behaving strangely—it was my husband! When I pointed out the puzzling and even unintentionally offensive things he had said, he agreed with me. (I know I’ve been picking on my husband in this blog post, but I’m sure my own perception of my interactions with others is just as skewed!)

Seldom does complete truth belong to any human disclosure, indeed.

I’m surprised it’s taken so many years of teaching and studying Emma to learn this truth in my own life. My loyalty to those I love must be tempered with the knowledge that none of their stories—or mine—are completely true.

Our perceptions are so unreliable sometimes. Just as you said — one conversation, two perceptions. I was thinking about something similar today as I drove to work. I was thinking about how I completely dismiss people who press certain buttons for me. If I perceive them to be arrogant, manipulative or hypocritical (my buttons), I simply dismiss them and all they have to say. I don’t seem to credit them with any good points or consider that perhaps they may say something valuable. I simply decide that the truth about them is exactly what I believe it to be and I dismiss them and their whole conversation. In the car this morning I found that I really don’t think I like this new revelation about myself. I much prefer to think that my truth is the true truth. So much more comfortable! (And yes, I do intend to keep my rose-colored glasses firmly in place! … because when they slip, I don’t much like what I see.)

Thanks for your insights, JT. What you say reminds me of the old chestnut, “There are three sides to every story: your side, my side, and the truth.” 🙂

“How is this text (or class) relevant to my life?”

How do you know where you’re going if you don’t know where you (or your ancestors) have been?

Historian, yes, yes, yes! I also don’t understand why some people don’t think knowledge is valuable for its own sake. One of the many reasons I love to study history is to learn about times and places and lives that are DIFFERENT from my own.

I think that unrestrained loyalty to family, and by extension to one’s tribe, leads to a host of other evils in society: self-deception (you don’t see how bad the ones you love really are), nepotism, omerta, blood feuds, tribal warfare.

I agree, MH. The problem for me is how to recognise when my loyalty is blind or unrestrained. In theory I know my loved ones are not always right any more than I am, but in practice . . . not so easy.